- Dale Ludwig Meetings, Myths Debunked, Presentations

Many presenters ask us about the best way to get their presentations started. They say that once the conversation gets going, they’re fine. But getting through the opening is always uncomfortable. Getting past the presentation nervousness that builds up before and at the start is a struggle.

This is a tough issue for us to address as well because there are so many issues contributing to the struggle. Fundamentally, though, a successful start requires a fully engaged presenter, one who is able to adapt what has been planned to what’s happening in the moment. Achieving that level of success is met with two significant challenges.

- Many presenters use techniques like scripting or memorization to get through the opening. This leads to the hard start found in speechmaking or other performances. It makes the beginning of the presentation feel like a curtain going up, and suddenly “you’re on.”

- The beginning of a presentation usually involves some level of nervousness for the presenter, sometimes a great deal of nervousness. Presenters need to know how to work through their nervousness as efficiently and effectively as possible.

The Handoff – The Secret to Reducing Presentation Anxiety

Let’s talk about the need to avoid speechmaking techniques first. Since business presentations are a type of conversation, they need to be initiated in a way that’s appropriate for that type of interaction. Think about a typical everyday conversation. Let’s say you’re walking down the hall with a co-worker after a staff meeting. As you walk, the two of you chat about what just happened at the meeting. One of you said something. The other responded, and the conversation was underway.

When your presentations begin, it’s essentially the same situation. The conversation should feel like a natural extension of what happened just before it. Rather than the hard start of a speech, beginning a presentation is more like accepting the baton from the person who just finished speaking — or maybe picking up where the last meeting left off. Your job is to continue the conversation and place what you say in the context of what’s happening in that moment. Just as the staff meeting conversation in the hallway didn’t spring out of nowhere, your presentations shouldn’t feel that way either.

When scripting or memorization are used at the beginning of a presentation, you run the risk of ignoring what’s come before. The baton is dropped.

To show you what I mean, let’s go back and look at what happened during the staff meeting you and your colleague attended. The major topic of conversation during the meeting was year-end planning. There were projects to prioritize and wrap up, a vacancy that needed a new job description before it could be posted, and low customer service scores to address, a major concern for upper management.

During the first part of the meeting, all of these issues came up. Some people thought that the multiple projects the department was working on had pulled people away from their regular responsibilities and contributed to the low scores. Others said that whoever was to be hired to fill the vacancy had to have more experience with customer interactions than the person who held the position before. Everyone was surprised by how low the service scores had been and were committed to improving them quickly.

The discussion was lively and productive. Before the meeting, Billie and Amber had been assigned to put some ideas together about the low scores. Were there any easy fixes that could be put into place right away?

Billie and Amber took this assignment and were ready to present their ideas. The problem was when Billie stood up to deliver her presentation; she said this:

“Hello, everyone. I’m sure many of you already know our customer satisfaction scores are lower now than they were a year ago. Turning the scores around is a high priority for management. Today I’d like to go over the recommendations Amber and I have come up with to turn things around.”

This is the opening that Billie planned the day before the meeting, and it made sense at the time. But by beginning her presentation this way, Billie completely ignored the conversation that had just taken place at the meeting. She stated the obvious (that the scores are low) and the unnecessary (that management wanted to see a change). She also implied that the conversation of the meeting was over because she and Amber were about to make their recommendations.

If Billie had used what happened during the meeting to start her presentation, the handoff to her would have been much smoother and appropriate.

“As you all know, Amber and I were asked to put some thoughts together about how we can bring our scores up. From what we’ve discussed so far today, I can see that you all have some great ideas already. So, what I’d like to do is go through the thinking Amber and I did and connect it to what you all have said. There are a lot of really good connections, and some of your ideas enhance ours. By the end of this, I think we will have excellent short- and long-term solutions.”

Billie’s second version does much more to fit her presentation into the context of the meeting. She demonstrated that she was prepared, aware of what was going on in the room, and ready to use everyone’s thinking to find a solution.

To help presenters with this kind of handoff, we encourage them to think of the introduction as a frame for the conversation that is about to take place. Here’s a link to the Framing Strategy Worksheet we use to do that.

Turning Nervousness Around

The beginning of a presentation is also complicated by the fact that there is usually some level of nervous anxiety associated with it.

For some presenters, nervousness results in a high level of self-consciousness and very low self-awareness, a discomfort so extreme that these presenters often don’t remember things they said or did when the presentation is over. Other nervous presenters might second guess what they’ve said, feeling that a clear explanation was bumbled. Observable signs of nervousness might be a fast speaking pace, low volume, fidgeting, or low energy.

No matter what it looks, sounds, or feels like, nervousness undermines the success of the presenter because it stands in the way of the conversation and the engagement it requires.

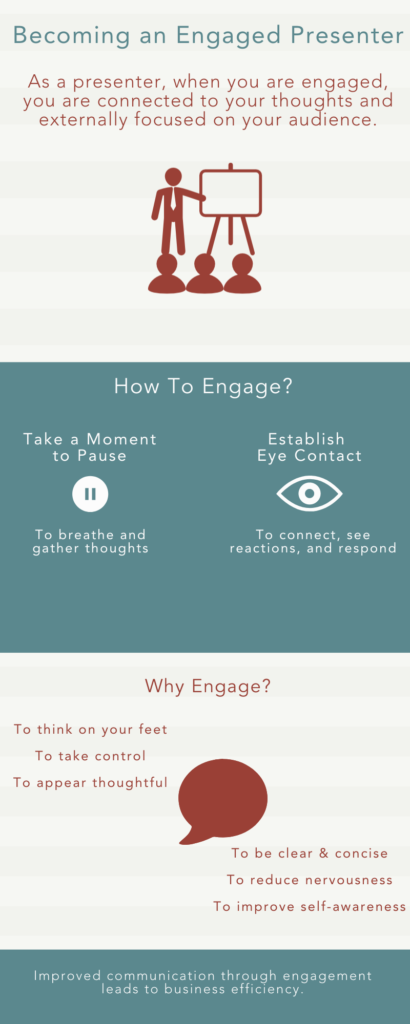

We look at nervousness in a new way. Not as something that can be prevented before the presentation (which is what traditional advice is all about, most prominently the “Practice makes perfect” myth). Instead, we treat nervousness as a type of anxiety or unease that turns a presenter’s thoughts and focus inward, away from the audience and away from what is happening in the moment.

To reverse the inward turn, we work with presenters to focus outward and on the present, toward the audience and what is happening now. When that connection is made, things start to feel familiar and much more comfortable. Racing thoughts are brought under control. Individuals in the audience are seen, and a conversational connection is made.

Reaching this level of engagement requires the intentional use of two skills: eye contact and pausing.

- The presenter shouldn’t scan the room quickly or look over people’s heads but establish solid, make-a-connection eye contact. They really need to see individuals in the audience.

- Pauses are periods of silence that the presenter uses to breathe and think.

Both of these skills are a challenge to apply when you’re in the throes of nervousness. It feels unnatural to look at people when they are the reason for your nervousness. The silence of a pause feels uncomfortable and risky when you’re anxious about sounding knowledgeable and prepared. These reactions are something that presenters need to make peace with. They need to believe that the discomfort of extended eye contact and the silence of a pause will very quickly begin to ease their nervousness. Through them, they will be engaged in the conversation, and the audience will be there with them.

Here’s an infographic to help.

Remember to check our resource page for regular educational posts on topics like this and more.